In 2003 Winsome Pinnock was described as the "Godmother of Black British playwrights" - and the label has stuck. She has a new play at the Royal Exchange theatre in Manchester which digs into attitudes in Britain to the historical slave trade between Africa and the Caribbean.

In 2003 Winsome Pinnock was described as the "Godmother of Black British playwrights" - and the label has stuck. She has a new play at the Royal Exchange theatre in Manchester which digs into attitudes in Britain to the historical slave trade between Africa and the Caribbean.

Pinnock has encountered several people lately who were convinced British playwrights had already written about British involvement in the African slave trade - finally outlawed in 1833.

"In fact until recently almost no one here had written about it," she says. "I suspect people remember certain films or they think of the African American plays which have been produced over the years. But that's not our story."

By "our story" Pinnock means all Britons, regardless of skin colour.

"This year there have been at least three new plays which do focus on Britain and slave trading but it's new territory. People should think about what that omission says about our willingness to talk about those events."

ELLA MAYAMOTHI

ELLA MAYAMOTHI

Now in her 50s, Pinnock was born in London to Jamaican parents. Her mother was a cleaner and her father worked at Smithfield meat market. "They were the Windrush generation," she says, "and often it wasn't easy for them." Her first full-length play was Leave Taking in 1987 which echoed parts of her parents' life.

She's had around 20 plays produced since, illuminating the black British experience perhaps more than any other writer for the stage.

Rockets and Blue Lights doesn't take a straightforward approach to Britain's involvement in the slave trade. Half is set in modern Britain and half in the 1840s when painter JMW Turner is working on his painting The Slave Ship. The picture's generally assumed to have been inspired by the maritime Zong massacre of 1781.

The Zong was a ship belonging to Liverpool merchants which sailed to Jamaica laden with slaves from Accra in what is now Ghana. Almost half the slaves were thrown overboard to drown so the ship's owners could claim insurance money (they later claimed they'd run out of drinking water). Eventually the horrific murders became public knowledge and contributed to abolitionist sentiment in Britain in the 1800s.

ELLA MAYAMOTHI

ELLA MAYAMOTHI

In the modern 21st Century sections of the play we see Lou, a black British actress played by Kiza Deen, who has been cast in a film retelling the story.

Pinnock says Turner's painting isn't as well-known as it might be because it belongs to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. "If it were in Britain it would force us to have a real conversation about the history it depicts. It's a really important image."

It's more than 30 years since Pinnock began to make a name for herself writing for the stage. "But for most theatre writers you accept it's a long apprenticeship.

"It takes years to find out what you can do with theatre and when you're older hopefully you've internalised all that hard-won craft and experience. You sustain your career by engaging with life and with your own life - that's all any writer has.

ELLA MAYAMOTHI

ELLA MAYAMOTHI

"When I was a young writer I was really afraid that eventually you come to an end. But now I realise you go through different stages all your life and your writing changes with that.

"But it can be scary because you see the emphasis in theatre on youth and you think they'll see you as some old fuddy-duddy."

She mentions Caryl Churchill (who's 81) as someone whose long writing career she admires. "Her most important work has come later in life, which is a big encouragement.

"But statistics show that women have always been less likely to have their plays produced - especially in the bigger spaces. So it's amazing to be at the Manchester Royal Exchange with Rockets and Blue Lights."

When Pinnock started out, a black British female writer was rare. Her play Leave Taking started life at the Liverpool Playhouse but went on to become the first play by a black woman staged at the National Theatre.

"A couple of years ago it was given a new production by the Bush Theatre in London and I hadn't read it for a long, long time.

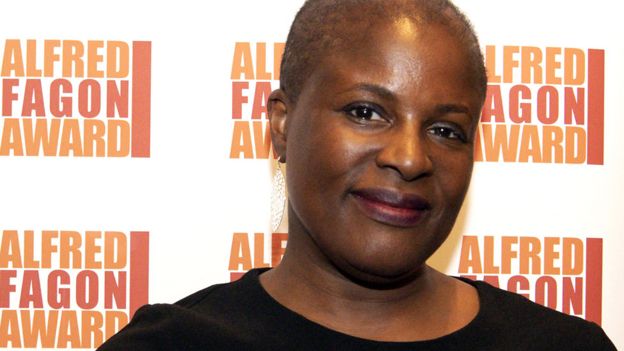

RICHARD H SMITH/ALFRED FAGON AWARD

RICHARD H SMITH/ALFRED FAGON AWARD

"But it still resonated with people and sold out its run. It was just chance that at that time the Windrush scandal had broken.'' (Some Caribbean people were threatened with being sent back although they had been in Britain for decades.)

"My 30 year-old play had referenced this. A character says you could be kicked out of the country if you don't get your papers in order. It made me think that often if you're in a specific group like black writers or female writers you seem ahead of your time because other people haven't heard your arguments or the stories you want to tell.

"It gave me hope that long after I'm gone some of my plays may still seem worth staging. But if Leave Taking still seems relevant all these years later that means there really hasn't been change since 1987. My play spoke to a new generation because in some fundamental way society hadn't changed as much as people thought it had."

Pinnock has reached a stage where she's much in demand to sit on panels discussing the black voice in British playwriting. Is it a topic she'd prefer to move on from?

"The organisers want you to talk about women in the theatre or black people in the theatre. And you hear other people say, 'oh I'm so fed up talking about this'.

"But I think, 'why haven't you still got the energy to fight?' This kind of equality isn't somehow going to happen overnight - so you'd better be prepared still to be talking in 20 years' time. When things change, that's when I'll stop talking about it."

Comments